In brief

Many very different systems keep stumbling onto similar strategy patterns because the space of workable solutions is funnelled by three kinds of constraint: what the solver is like, what the game rewards, and what the world physically or institutionally allows to work. Most theoretically possible moves are never even seen; many that are seen fail on contact with reality. A small set of ‘strategy archetypes’ sit in the overlap between what is easy to imagine and what is hard for the environment to kill, so camera‑like eyes, logosyllabic scripts, familiar succession plays, compromised insiders, and certain algorithmic tricks keep getting rediscovered in isolation when agents explore similar terrain.

If we take that seriously, strategy stops being a hunt for one‑off clever moves and becomes an exercise in mapping the constrained option space you actually inhabit. You assume from the start that you are moving inside a narrow basin that many others have already explored, and the job is less to conjure novelty than to read that landscape honestly: be explicit about who the agent really is, what the payoff structure actually rewards, and what the substrate makes cheap, costly, or impossible. The real advantage is not found in chasing originality for its own sake, but in recognising which archetype you are enacting and deciding, deliberately, whether to run it more cleanly or to do the slower, harder work of altering the constraints so that a different class of strategies becomes viable at all.

A quick note on scope and limitation

This essay does not pretend to offer a grand unified theory of convergence I acknowledge that the blind selection of a gene is distinct from the cognitive intent of a statesman. The argument in this essay is narrower. It is not that biology and history share a single mechanism, only that they are shaped by a similar geometry that rewards some patterns and penalises others. Similarity implies structural analogy rather than mechanical identity. I know this analogy has holes. Nature is ruthless and fast; human history is messy and slow. It’s hard to tell if a strategy repeats because it works, or because leaders copy each other. I don’t have a perfect answer for that yet, but I think the constraints eventually force the same hand.

The framework I propose also differs from a simple taxonomy. Classification is static. It sorts results. I am interested in the process that produces them. I have also deliberately excluded examples of divergence. History and evolution are filled with unique variations and systems that do not converge. I’ve omitted them because explaining the rule is easier if we temporarily set exceptions aside. A future extension will address outliers that take the rarer paths these constraints allow.

Convergent isomorphism

We often assume the universe offers infinite ways to solve a problem. We assume that if we replayed the tape of history or biology, the outcomes would diverge wildly. When we examine systems separated by vast distances or distinct eras, the record suggests the opposite. Distinct lineages lock into strikingly similar configurations. Whether one looks at the anatomy of an eye, the syntax of a script, or the mechanics of a political purge, the solution space does not resemble a wide-open plain. Seen from far enough away, it looks less like an open plain and more like a funnel.

When I talk about convergence here, I do not mean a single kind of similarity. Sometimes it is functional, where different designs solve the same problem in roughly the same way, as with antifreeze proteins that prevent ice crystals from growing. Sometimes it is structural, where distant lineages arrive at a similar architecture, such as the camera eye. Sometimes it is strategic, where different actors discover the same sequence of moves, for example, seizing the purse and the crown or recruiting compromised insiders. At other points it is an outcome, where many paths lead to a similar macro state, such as a centralised empire or a literate bureaucratic state. In what follows, I am mainly interested in strategic convergence, the recurring logics of action, although functional and structural convergence frequently accompany it.

Clay, cattle, code

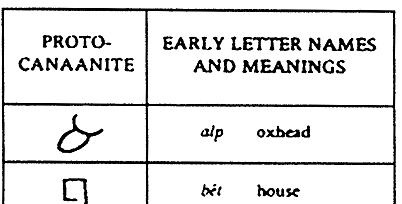

In Uruk, around 3200 BCE, Sumerian scribes evolved their script from literal drawings of oxen to abstract cuneiform wedges. To capture complex language, they detached the symbol from the object and attached it to the sound. Linguists call it the rebus principle.

Thousands of years later, Maya scribes in Mesoamerica followed an almost identical path. They operated in complete isolation from Sumerian influence. They began with logograms for items like ‘stone’ (TUUN) and eventually repurposed them to represent the phonetic syllable ku (Coe and Van Stone, 2005).

This path from picture to sound wasn’t a one-off statistical outlier. The Egyptians did it. The Chinese did it. Working in relative, or in the case of the Maya, complete isolation, scribes across these cultures discovered the same set of fundamental insights: that pictures can represent sounds, that simple elements can combine to build complex meanings, and that abstract markers can establish grammatical relationships (Houston, 2004).

These cultures theoretically had a vast artistic canvas, but they never began with a blank slate. Scribes were already constrained by their media, their tools, and the pattern recognition systems of the human brain. Hands favour discrete strokes. Eyes track line junctions. Clay tablets and brushes impose material limits. Administrative needs favour speed and legibility. Within these constraints, early scripts could in principle have stabilised in many different directions. Yet we see closely related logosyllabic systems emerging independently. Pictures are repurposed to stand for syllables. A manageable inventory of signs combines to build complex words. Additional markers indicate grammatical relations.

Writing systems would later diverge. But at the threshold of state-level literacy, when scribes needed to encode complex language quickly and in a form that could be learned, the constraints of the human visual system and the demands of bureaucratic record-keeping created a strong attractor. The option space was large, but the geometry of the problem narrowed independent searches toward a recurring architectural pattern.

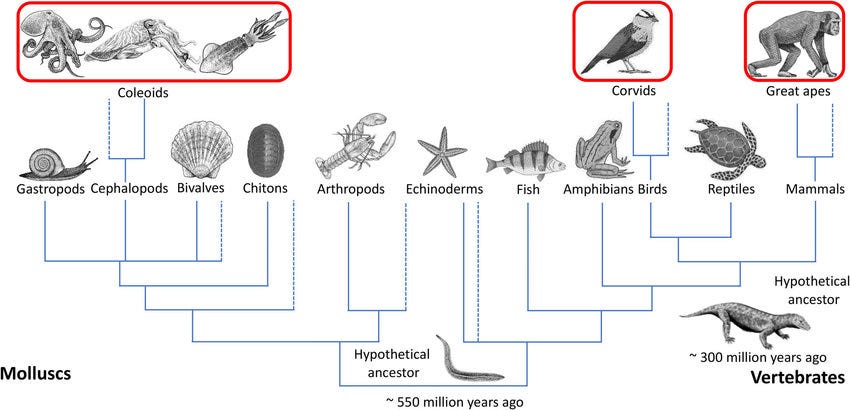

Biological convergence

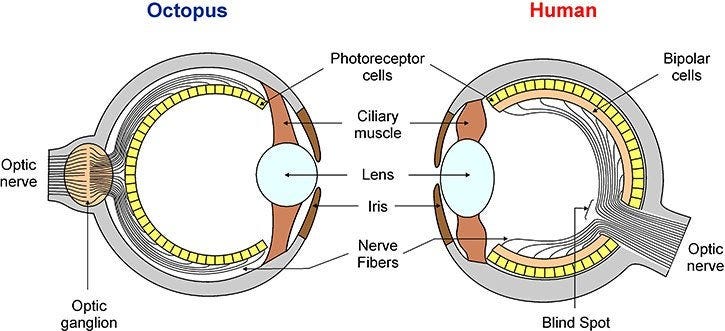

The human eye and the octopus eye are near-identical in functional design. Both rely on a single lens, an iris, and a retina packed with photoreceptors.

Yet the last common ancestor of humans and molluscs was a blind worm 600 million years ago (Erwin and Davidson, 2002).

They share genetic tools, but they don’t share a blueprint. What they share is a problem. Physics dictates how light travels. If you want to resolve a clear image on a small surface, the laws of optics only offer a few viable designs. Nature wasn’t copying itself; it was bumping into the same walls.

The atmosphere applies a similar mechanical discipline to flight. Pterosaurs, birds, and bats evolved flight independently across millions of years. Their ancestries are distinct, but their engineering logic is constrained and convergent. Pterosaurs stretched a membrane along a finger (Williams, 2002). Birds fused bones to support feathers (Mayr, 2017). Bats stretched webbing between digits (Simmons et al., 2008). Despite these anatomical differences, they all converged on the high-camber aerofoil and lightened skeletal structures (Dudley, 2002; Mayr, 2017; Simmons et al., 2008).

The fluid dynamics of air require specific ratios of lift to drag. Physics does not care about the lineage of the organism. It only cares whether the wing generates enough lift to counter gravity. In W. Brian Arthur’s view, the bird and the bat are doing the same technological thing: ‘capturing a phenomenon’ (Arthur, 2009). Whether built by genes or engineers, a wing is a device for ‘programming nature,’ exploiting the consistent behaviour of airflow to produce lift. Because the physical phenomenon is fixed, the mechanism that captures it must converge on a single efficient form.

The narrowing becomes even sharper at the molecular level. Arctic cod and Antarctic notothenioids inhabit freezing waters at opposite poles. To survive, both species independently evolved antifreeze proteins. While the molecular structures show considerable diversity, they converge on the same functional solution: both evolved proteins that bind to ice crystals in the blood to arrest their growth (Davies, 2014). The thermodynamics of ice formation presents a rigid constraint. Whether the protein is globular or helical is secondary to the presence of an effective ice-binding surface. Out of the vast space of possible sequences, only a small family can satisfy this requirement. Evolution did not solve this problem twice by accident; it found similar functional solutions in a tightly constrained region of chemical space.

Substrate independence

Does a similar constraint geometry extend to human agency? The natural next question is whether the logic that narrows wings and eyes has an analogue in statecraft.

Comparing biology to politics risks a category error. Biological forms emerge through blind selection acting on random mutations. Political forms emerge through cognitive intent, deliberation and cultural imitation. The feedback loops also differ: in biology, failure is often immediate and fatal; in politics, ineffective strategies can persist through coercion, ideology or luck.

Even so, human problem-solvers do not escape constraint. Cognition can be seen as a fast internal filter layered on top of slower external feedback. A general does not need to lose a war to test a flawed strategy; they can model the defeat in their mind and discard the option before implementation. Evolution prunes designs by killing organisms that take the wrong turn. Human agents prune designs by anticipating those turns. In both cases, selection happens inside a structured environment; the mechanisms differ, but the pattern of constraint is analogous.

This similarity is most visible at a broad scale, even in isolation or with limited diffusion. Medieval Europe and Japan offer a striking, if imperfect, parallel. Faced with a weak central state and a lack of currency, both societies drifted toward a similar solution for resource allocation: the exchange of land for military service. The samurai and the knight developed in parallel (Strayer, 1968). The institutional details and the cross-cultural use of ‘feudalism’ are contested, but the underlying trade recurs when centres are poor in cash but rich in land.

A similar logic appears in mass violence. The sequence is familiar: classify an enemy, degrade their moral status and routinise harm. This dehumanisation pattern appears in the Roman proscriptions and the Cambodian killing fields. It recurs not because perpetrators compare notes, but because it is a particularly reliable psychological mechanism for bypassing the human inhibition against killing. Other routes exist, including obedience to authority and diffusion of responsibility, but this script is one of the most frequently reused. The recurrence does not require collusion; it reflects how these mechanisms solve repeated strategic and psychological problems.

The environment acts as an analogous filter. In biology, feedback is often hard and fast; unfit designs are eliminated quickly. In politics, feedback can be soft and delayed; weak strategies can persist through coercion, ideology or luck. Over time, however, strategies that ignore core constraints tend to be penalised, and a small family of viable archetypes persists.

The distinction between path and destination matters. A focus on structure does not deny the reality of chaos. As I explore in my analysis of modern brands, human systems are defined by non-linearity; they are prone to sudden phase transitions where a single tweet or a random error can trigger a cascade. But this volatility operates within a basin of attraction. The specific route a system takes may be chaotic, but the walls of the funnel remain rigid. The butterfly effect might determine which specific warlord seizes the throne, or the exact date the coup succeeds, but it cannot alter the structural necessity that the throne must be secured and the treasury seized. The path is subject to chance; the destination is subject to constraint.

The succession script

The same convergence appears in the mechanics of power transfer. When the central authority dissolves, the vacuum creates a rigid geometry. Legitimacy generally requires both symbolic authority and material resources.

In 1259, Kublai Khan secured the fiscal resources of China while his rival seized the symbolic capital (Rossabi, 1988). In 1135, Stephen of Blois seized the English treasury before racing to London for the coronation (King, 2010). In the War of the Spanish Succession, rival claimants established parallel courts to secure this dual validation (Kamen, 2001). The succession script follows a stubborn logic. A contender who fails to secure both the symbol and the purse risks elimination by one who does.

Negative definition

The creation of political identity follows a similar constraint. Unification often requires an external negative. Shaka Zulu constructed a state in the 1810s by defining it strictly against rival groups (Hamilton, 1998). Simultaneously, Simón Bolívar defined ‘Gran Colombia’ against Spanish colonial identity (Lynch, 2006). The Qin dynasty, the Romans, and the Greeks all consolidated internal power by defining the external ‘barbarian’ (Di Cosmo, 2002). They are active tools of consolidation through exclusion, not mere linguistic quirks.

The information trap

Counter-insurgency forces an even tighter collapse of the solution space. An occupier needs information but faces an opaque population. Direct interrogation fails due to a lack of trust.

Such a deadlock forces the occupier to recruit a traitor. The Soviet Cheka developed the seksoty network (Leggett, 1981). British forces in Kenya developed pseudo-gangs (Anderson, 2005). The Phoenix Program in Vietnam relied on similarly turned informants (Moyar, 1997). While diffusion and copying might have played a role, they converged on this strategy mainly because the structure of the network offered one of the few viable entry points.

Institutional camouflage

Deception is not limited to the shadow war. It often becomes a structural requirement for the throne itself. Naked power invites resistance; durable power frequently masks itself in tradition.

Augustus retained the Senate while ruling as emperor (Zanker, 1988). The Tokugawa shoguns ruled as administrators for a figurehead emperor (Jansen, 2000). Napoleon used the Pope to sanctify a revolutionary crown (Zamoyski, 2004). These leaders independently discovered institutional camouflage. To stabilise quickly, a new order often finds it easiest to occupy the visible shell of the old.

The structural blindness

It is this relentless, repetitive, almost eerie sameness that demands attention. When we see the same scripts playing out across disconnected empires and eras, it becomes difficult to view history as a series of unique events. The seed for this analysis came from a conversation with a friend regarding this exact phenomenon. We were discussing the recurrence of mass violence. You can certainly describe these events as specific tragedies caused by specific monsters, and there is an obvious emotional clarity in doing so. We look at a dictator or a war, and we focus on the unique evil of that moment.

But I always found this narrative approach misleading at best and dangerous at worst. We claim we must ‘learn from history,’ yet the patterns of suffering recur with mechanical precision. A purge in ancient Rome follows a script that is hauntingly similar to a purge in the 20th century.

By obsessing over who did what, the ‘great men’ and the villains, we miss the how. We ignore the underlying structure that keeps producing the same outcomes. Scholars like Peter Turchin have mapped these forces for decades, yet our public discourse remains trapped in the specific, treating history as a sequence of isolated moral choices.

I started this project to understand human suffering, but it forced me to look wider. The logic that drives a purge is not the same as the logic that shapes a wing, but both can be described in terms of agents moving within a constrained landscape, with harsh feedback for certain moves and rewards for others. What began as a critique of historical narrative evolved into an attempt to map a general framework for convergence. To understand why the horror repeats, we have to look past the moral intent of the actors and examine the constraints that shape the game itself, whether that game is played by kings or by genes.

The constraint architecture

The mechanism becomes clearer once we distinguish between the possible and the viable. The recurrence of the camera eye or the compromised spy is not proof that the theoretical option space is small. Evolution produced eyespots and compound lenses, which remain viable in other contexts, before selecting the single-lens design for high-resolution vision. On paper, Kublai Khan also had a vast array of tactical options.

Convergence occurs because a strategy is never selected in a vacuum. It is the product of a dynamic interaction between the source of a constraint and the timing of its application.

This framework comes from Herbert Simon’s distinction between an ‘inner environment’ and an ‘outer environment,’ and his ant-on-the-beach parable (Simon, 1996). The ant’s jagged path mostly reflects the bumps and ridges of the sand, not some elaborate inner complexity. In Simon’s terms, any artifact (a tool, an organism, an institution) sits at the interface between what it can do and the world it has to do it in.

Because I want to talk about convergence in evolution, statecraft, and computation together, I push his picture a step further. I call the inner environment the agent, to emphasise that the constraint is not just biology or code but also history: training data, doctrine, institutional memory. An ant, a general staff college, and a large language model have very different inner environments, but in each case, what matters is the kind of search they make easy and the kind they almost never attempt.

I also split Simon’s ‘outer environment’ into two pieces: incentive and substrate. The incentive is the selective pull, the payoff structure that says what counts as winning (fitness, revenue, office, legitimacy). The substrate is the medium that pushes back: biochemistry, airflow and bone, clay and bureaucracy. The incentive tells you the rules of the game; the substrate is the physics of the board. A metaethnic frontier in imperial history and a rigid network protocol in computing look less alien to one another when you see them this way. Both are hard constraints that narrow the range of moves that work, and both can drive very different agents toward the same few recurring forms.

Three sources of pressure, then, shape the funnel. These act as the ‘fields’ that generate the constraints:

The agent (internal constraints): No solver ever starts from a genuinely blank slate. They bring a specific architecture and history. Evolution operates on an inherited genetic toolkit. It is bound by phylogenetic constraints: developmental pathways that make certain forms metabolically cheap and others impossible (Gould and Lewontin, 1979).

Human solvers are bound by the cognitive machinery of the hominid brain. Scribes in Sumer and Mesoamerica shared eyes that track in saccades and brains that chunk information into hierarchies. These biological rails guide the initial search (Dehaene, 2009). A dolphin will never invent cuneiform because it lacks the manipulative morphology.

The incentive (game theoretic constraints): The problem contributes the rules of the game. It defines the win state and the payoff matrix (Maynard Smith, 1982). A succession crisis has a fixed structure. Power is vacant. Multiple claimants exist. Only one can hold the monopoly. This topology constrains the logic of the move. To ignore the treasury or the symbolic capital is to exit the game. The player does not choose these objectives. The structure of the crisis imposes them.

The substrate (physical constraints:) The world adds the hard laws of physics. Air has a specific viscosity. Light travels in straight lines. Ice crystallises according to thermodynamic laws. These are non-negotiable. The substrate is not just a passive container; it is a collection of physical phenomena waiting to be exploited. If an organism requires flight, the substrate demands a specific lift-to-drag ratio. If a fish requires liquid blood in sub-zero water, the substrate demands a specific molecular interference with crystal growth.

In human systems, the substrate also includes technologies, institutions and information infrastructures. A bureaucratic state, a patronage network or a digital platform each make some strategies cheap and others prohibitive. These constraints are softer and more reversible than physics, but they still shape which options are realistically available and which converge across cases.

These three fields tell us where constraint comes from. To see how they create a funnel, we also need to know when they act.

They do not all act at the same time or with the same weight. They operate through a two-stage sequence where different forces dominate at different times. The interaction creates a funnel.

First is search bias. It is the generative filter. This is Simon’s bounded rationality seen from the outside. It determines what gets tried. At this stage, the agent is the primary constraint. The solver does not scan the entire theoretical horizon. It scans only what its internal architecture allows. A dolphin cannot conceive of cuneiform because its biological toolkit renders the option invisible. The substrate plays a secondary role here by offering affordances, much as clay makes wedge shapes cheap to discover. For cognitive agents, the incentive also shapes the search. A general anticipates the rules of war and prunes losing strategies before proposing them. But the main limit is internal. The option space collapses from a notional infinity of possibilities to a narrow wedge of plausible attempts.

Second is selection pressure. This is the terminal filter. It determines what survives contact with reality. Here the agent loses its influence and the environment takes over. The substrate acts as a physical veto. If a wing design does not generate lift, gravity eliminates it. The incentive acts as a strategic veto. If a succession plan ignores the treasury, the rival eliminates it. Once a strategy is attempted, the internal preference of the agent no longer matters. The world only asks if it works.

An archetype is just a solution the agent can generate, and the environment lets it survive. When a path is easy for the agent to find and difficult for the environment to kill, it becomes an attractor.

A path can be viable but undiscoverable. It exists in possibility space but no agent will find it because search bias prunes it. A path can be discoverable but unviable. It is easy to try but physics or the payoff structure kills it. The archetype is the rare solution that passes both filters. It is both discoverable and viable.

I’ll use two terms for clarity.

Option space: We borrow this concept from the action space of reinforcement learning. It is the set of all moves an agent could execute if it were not bound by cognitive or biological limitations.

Strategy archetype: An archetype is just a solution the agent can generate, and the environment lets it survive. In Simon’s terms, this is the artifact: the successful ‘interface’ where the inner environment of the agent meets the outer environment of the world. An archetype is simply an artifact that recurs. It sits in the region where the search bias of the agent (what is findable) overlaps with the selection pressure of the substrate (what is viable). When a path is easy for the agent’s bounded rationality to discover and difficult for the substrate’s physics to destroy, it becomes an attractor.

Algorithmic convergence

History and biology are messy. To see the mechanics of convergence more clearly, we can examine a domain where the rules are explicit and performance is measurable: computer science.

Take the problem of sorting. The objective is to arrange a shuffled dataset into an ordered sequence.

The incentive: Order the data as efficiently as possible, subject to constraints on time, memory and implementation cost.

The substrate: The processing speed of the CPU and the latency of the memory.

The agent: The designer or optimisation process choosing how to organise the data.

The option space

For comparison‑based sorting, information theory sets the geometry. The theoretical space of possible sorting algorithms is huge. Any systematic procedure for comparing and rearranging elements constitutes a valid algorithm. We could devise an algorithm that compares every element with every other element. We could sort in pairs, in triplets, recursively, iteratively, or by building auxiliary structures. The combinatorial space of possible comparison-and-swap sequences is effectively unbounded.

Yet despite decades of work by thousands of programmers, the algorithms that survive in production systems cluster into a small number of recurring strategic families.

Selection pressure (time complexity)

Selection pressure here operates through multiple dimensions. Time complexity measures how the number of operations scales as the dataset grows. Space complexity measures memory overhead. Stability matters when equal elements must preserve their original order. Cache efficiency affects real-world performance. Different applications weight these pressures differently, but all impose constraints.

When we visualise different sorting algorithms processing the same data, the gap between efficient and inefficient designs becomes visible:

Strategic families

Behind the dozens of named sorting algorithms, there are recurring strategic patterns.

Incremental construction (insertion sort, selection sort): Build the sorted sequence one element at a time. Simple to implement and efficient for small datasets or nearly-sorted data. Time cost grows quadratically, O(N²), making them unviable for large random datasets. Yet they persist in niche contexts and as components of hybrid strategies.

Divide-and-conquer hierarchies (merge sort, quicksort, heapsort): Decompose the problem into smaller subproblems, solve recursively, and combine results. This reduces the time cost to O(N log N). Just as Sumerian scribes and Maya bureaucrats converged on hierarchical structures to manage state records, computer scientists converged on hierarchical decomposition to manage comparisons. The substrate of information processing penalises flat iteration and rewards recursive subdivision.

Distribution-based sorting (radix sort, counting sort, bucket sort): Exploit structural properties of the data itself to avoid pairwise comparisons entirely. When applicable, these can achieve linear time, O(N). They represent a fundamentally different strategy, trading generality for efficiency in specialised contexts.

Hybrid strategies (Timsort, Introsort): Modern production systems often combine families. Python and Java use Timsort, which switches between merge sort and insertion sort based on data characteristics. C++ uses Introsort, which begins with quicksort, switches to heapsort if recursion goes too deep, and finishes small partitions with insertion sort. These hybrids reveal that the solution landscape contains multiple local optima, not a single global peak. The persistence of diverse strategies reflects different selection pressures in different contexts.

What I am calling a strategy archetype inside this technical setting is very close to a domain-specific module: a solution shape that, once discovered, becomes part of the standing grammar future designs are written in.

Substrate shift: from RAM to disk

The role of the substrate is easiest to see when the physical environment for a task like sorting changes, because sorting in memory assumes cheap, uniform access to any element, but once data lives on spinning disks where a mechanical head has to move to each location and seek time dominates performance, the goal quietly shifts from minimising comparisons to minimising disk reads, and database engineers converge on structures such as B-Trees with wide, shallow branching that cut down the number of seeks needed to find a key.

What counts as a good way to keep data ordered depends on whether you are dealing with RAM, disks or solid-state drives, and the physics of storage ends up shaping which strategies are even worth considering.

Convergence beneath diversity

This domain shows both convergence and context-dependence. The option space is vast, yet independent designers converge on a small set of strategic families. We do not see a single optimal algorithm, but we do see recurring patterns: hierarchical decomposition, incremental construction, exploitation of data structure, and hybrid switching between strategies.

Search bias makes some strategies easier to discover. Selection pressure favours those that align with the constraints of the substrate and the demands of the problem. As the environment shifts from RAM to disk to solid-state storage, the winning archetype shifts with it, but the viable families remain bounded and repeatedly rediscovered. The point isn’t to prove uniqueness; it’s to show how constraints narrow a huge theoretical range into a small set of recurring solutions.

The discovery engine

In a sense, the logic reframes innovation. Efficient strategies emerge as much from the structure of the problem as from the designer’s imagination.

This distinction is clearest in the case of AlphaZero. The network began its training with nothing but the rules and a win condition. It had no access to historical games.

Within hours, it began playing the Evans Gambit (Sadler and Regan, 2019, p. 75). It did not copy this from a database. It converged on the strategy because the geometry of the board renders it a potent attractor. You can make a plausible argument that Captain Evans did not invent the move in the 1820s; he merely exposed a latent property of the system.

The same logic applies to code. In 2023, AlphaDev discovered a way to optimise standard sorting algorithms by removing a single assembly instruction (Mankowitz et al., 2023). It found a shortcut in the processor’s option space that human engineers had missed for decades.

These systems do not invent ex nihilo; they explore patterns already latent in the problem’s constraints.

References [incomplete]

Arthur, W.B. (2009) The Nature of Technology: What It Is and How It Evolves. New York: Free Press.

Anderson, D.M. (2005) Histories of the Hanged: The Dirty War in Kenya and the End of Empire. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Bohush, V. (2016) Visualization of 24 Sorting Algorithms In 2 Minutes.

Coe, M. D. and Van Stone, M. (2005) Reading the Maya glyphs. 2nd edn. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd.

Davies, P.L. (2014) ‘Ice-binding proteins: a remarkable diversity of structures for stopping and starting ice growth’, Trends in Biochemical Sciences, 39(11), pp. 548-555. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2014.09.005

Dehaene, S. (2009) Reading in the Brain: The New Science of How We Read. New York: Penguin.

Di Cosmo, N. (2002) Ancient China and Its Enemies: The Rise of Nomadic Power in East Asian History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

DiMaggio, P.J. and Powell, W.W. (1983) ‘The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields’, American Sociological Review, 48(2), pp. 147-160. doi: https://doi.org/10.2307/2095101

Dudley, R. (2002) The Biomechanics of Insect Flight: Form, Function, Evolution. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Erwin, D.H. and Davidson, E.H. (2002) ‘The last common bilaterian ancestor’, Development, 129(13), pp. 3021–3032. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.13.3021

Gould, S.J. and Lewontin, R.C. (1979) ‘The Spandrels of San Marco and the Panglossian Paradigm: A Critique of the Adaptationist Programme’, Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B. Biological Sciences, 205(1161), pp. 581-598. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1979.0086

Hamilton, C. (1998) Terrific Majesty: The Powers of Shaka Zulu and the Limits of Historical Invention. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Houston, S.D. (2004) The First Writing: Script Invention as History and Process. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jansen, M.B. (2000) The Making of Modern Japan. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press.

Kamen, H. (2001) Philip V of Spain: The King Who Reigned Twice. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Kettunen, H. and Helmke, C. (2020) Introduction to Maya hieroglyphs. 17th edn. Wayeb.

King, E. (2010) King Stephen. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Land, M.F. and Nilsson, D.-E. (2012) Animal Eyes. 2nd edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Leggett, G. (1981) The Cheka: Lenin’s Political Police. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Lynch, J. (2006) Simón Bolívar: A Life. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Mankowitz, D.J. et al. (2023) ‘Faster sorting algorithms discovered using deep reinforcement learning’, Nature, 618, pp. 257–263. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06004-9

Maynard Smith, J. (1982) Evolution and the Theory of Games. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511806292

Mayr, G. (2017) Avian Evolution: The Fossil Record of Birds and its Paleobiological Implications. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell. doi:10.1002/9781119020677

Moyar, M. (1997) Phoenix and the Birds of Prey: Counterinsurgency and Counterterrorism in Vietnam. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press.

Ogura, A., Ikeo, K. and Gojobori, T. (2004) ‘Comparative Analysis of Gene Expression for Convergent Evolution of Camera Eye Between Octopus and Human’, Genome Research, 14(8), pp. 1555–1561. doi: 10.1101/gr.2268104

Rossabi, M. (1988) Khubilai Khan: His Life and Times. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Sadler, M. and Regan, N. (2019) Game Changer: AlphaZero’s Groundbreaking Chess Strategies and the Promise of AI. New In Chess. Available at: https://www.newinchess.com/media/wysiwyg/product_pdf/9073.pdf (Accessed: 2 June 2025).

Schmandt-Besserat, D. (2014) ‘The Evolution of Writing’, in Wright, J. (ed.) International Encyclopedia of Social and Behavioral Sciences. Elsevier.

Simmons, N., Seymour, K., Habersetzer, J. et al. (2008) ‘Primitive Early Eocene bat from Wyoming and the evolution of flight and echolocation’, Nature, 451, pp. 818-821. doi: 10.1038/nature06549

Simon, H.A. (1996) The Sciences of the Artificial. 3rd edn. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Strayer, J.R. (1968) ‘The Tokugawa Period and Japanese Feudalism’, in Hall, J.W. and Jansen, M.B. (eds.) Studies in the Institutional History of Early Modern Japan. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Tajfel, H. and Turner, J. (1979) ‘An Integrative Theory of Intergroup Conflict’, in Austin, W.G. and Worchel, S. (eds.) The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations. Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole, pp. 33-47.

Turchin, P. (2023) Structural-demographic theory. Available at: https://peterturchin.com/structural-demographic-theory/ (Accessed: 19 July 2025).

Vogel, S. (1994) Life in Moving Fluids: The Physical Biology of Flow. 2nd edn. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Williams, J.M. (2002) ‘Form, function, and the flight of the pterosaur’, Science, 297(5590), pp. 2207-2208. doi:10.1126/science.297.5590.2207b

Wright, S. (1932) ‘The roles of mutation, inbreeding, crossbreeding, and selection in evolution’, Proceedings of the Sixth International Congress of Genetics, 1, pp. 356-366.

Zamoyski, A. (2004) Moscow 1812: Napoleon’s Fatal March. London: HarperCollins.

Zanker, P. (1988) The Power of Images in the Age of Augustus. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. doi: 10.3998/mpub.12324